HISTORY OF MOTOR CYCLES DEN

THE Eagle AND THE Rising Sun

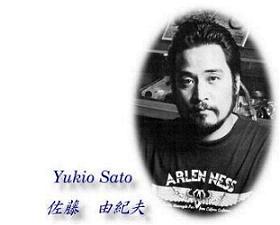

The afternoon light is fading fast when Yukio Sato appears in the doorway of his Rycroft Street motorcycle shop. For Sato, it is paw hana time. He has just finished a day's work on his latest creation the Titan-a revolutionary new motorcycle he will unveil in California next year. Sato is fast gaining a reputation as the world's foremost designer and builder of custom motorcycles. His cycles are works of art, each more exquisitely crafted than the last. When he is working, he is always thinking: How can I make it more efficient and durable? How can I make it stronger and more beautiful? The result of Sato's latest thinking is the Titan. He estimates it will last 100 years. "There is nothing like it," he says. "It is the best motorcycle in the world."

Sato is a 35-year-old native of Tokyo. He has sacrificed a secure position in Japanese corporate life to chase an American dream. Among other things, he has been a student of Zen and a friend of the Hell's Angels. His lifestyle combines elements of Japanese aesthetics and American entrepreneurship−a Samurai on wheels.This Particular evening finds him outfitted in jeans and a black,Sleeveless T−Shirt.His dark,black hair(which once fe11to his shoulders)is cut short, parted in the middle and brushed back on the sides. Bearded and  sporting a gold earring, he smokes Kool cigarettes and drinks Coors beers.

Inside Sato's shop there is the chaotic Jumble that one finds in most garages. Partially assembled Harley Davidson motorcycles are everywhere. The colors of the bikes are striking. One is New York taxi-cab yellow, another olive green, still another a fire engine red accented by coiled brass pegs.

sporting a gold earring, he smokes Kool cigarettes and drinks Coors beers.

Inside Sato's shop there is the chaotic Jumble that one finds in most garages. Partially assembled Harley Davidson motorcycles are everywhere. The colors of the bikes are striking. One is New York taxi-cab yellow, another olive green, still another a fire engine red accented by coiled brass pegs.

Sato conducts business in his shop-and in this case an interview-from behind a glass counter where many of his parts are on display. I am seated on one side of the counter in one of two black fiberglass high-back bucket seats with red foam cushions. Connected at the base by a metal shaft to a tire, these "chairs" look as if they were extracted from the cockpit of an Italian sports car. (Sato later tells me they were designed by a friend who is now in a joint venture with a leading Italian automaker). Since I do not speak Japanese and Sato's English is limited, both of us have interpreters. My questions are relayed to Sato through his assistant, Jimmy Asada. In turn, Sato's answers are fed back to me through my Japanese-speaking friend. It seems an awkward, cumber-some arrangement, but in practice a camaraderie develops that adds a wonderful dimension to the interview. Looking around, I notice a magazine rack on the left side of the counter filled with motorcycle periodicals: Easy Rider, Iron Horse, Goggle, Super Cycle.

A bumper sticker on the wall to my right asks, "Have you hugged your motorcycle today?" About the only thing in the shop that leads one to suspect that Sato has any interests beyond motorcycles are a pair of abstract paintings hanging on the wan behind him. The paintings remind me that he is an artist. He doesn't assemble motorcycles. He creates them. Everything-the design, the parts-is of his own invention, built by him. The theory that the Japanese are poor inventors but great imitators does not apply in his case. "I like everything about motorcycles," he says. "I like riding motorcycles. I like racing motorcycles. In Japan, I used to race a lot more than I do now, until I broke my left leg. I like to work on the mechanics of motorcycles. But What I like most is getting the creative idea-a new design idea, a performance idea and then expressing it. It's my artistic statement...The artist stands before the blank canvas, and whatever is inside of himself he draws on the canvas and creates a work of art. In my case, the canvas is a motorcycle. love affair with America and motorcycles began in 1964, at age 13, when he spotted his first Harley Davidson in the streets of Tokyo. Harleys were rare treasures in Japan at that time. Sato says he has a friend, now in his fifties, who bought a Harley after World War II. It cost about the same as a small house in Tokyo. Sato got his license-and his first motorcycles-when he was l6. He elongated the gas tanks on Honda and Tohatsu 50c.c.'s and turned them into racing bikes.

One day while he was out riding he came across a group of American servicemen a couple of whom were riding custom Harleys.

One day while he was out riding he came across a group of American servicemen a couple of whom were riding custom Harleys.

Sato had seen full-dress" Harleys before, but never a custom bike. "It was a decisive moment in my life," he says. ''After that, there was no turning back." Between the time he was 16 and 20, Sato figures he worked on about seven different bikes. he would get Honda 450s or Kawasaki 650 Cruisers and customize them so that they looked like Harleys. He got his first Harley-a 1971 Harley FX-when he was 20.

One wonders what his parents thought of all this? "My parents always knew I was a little crazy," he says. "When I was a kid going to school, I'd be drawing Pictures or doing sculptures when I was supposed to be studying math. I was lust that kind of kid. When I was a teenager and still living at home, we had a house with a walkway around it. I used to have my motorcycles up on blocks all around the house. Sometimes I would want to take one up to my room on the second floor and my parents would help me carry it up. So they were all for it. They knew it was useless to be otherwise After high school, Sato studied graphic design at a junior college and then went to work for an interior design business. At one point, he was putting in 50 to 60 hours a week as a designer arid in his spare time working on motorcycles in a garage he had rented from a friend.

Apparently he had a flexible arrangement with his employer, for over the next several years he made repeated trips to Hawaii and California.

As soon as he saved enough money, he was off. Wherever he went he would visit motorcycle shops looking for custom parts, because at that time there were custom parts in Japan. ''Coming home, I would trek through airports carrying a frame over my shoulder, wheels under my arms:' he says. He made his first trip to Hawaii when he was l9. He estimates he has made some 36 trips to the U.S. since

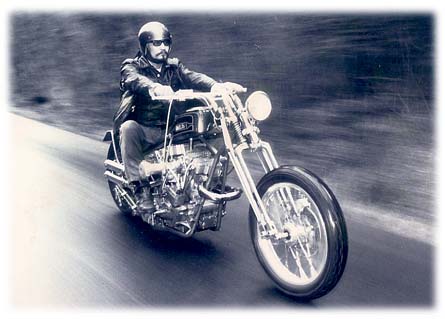

It was during these trips that he became acquainted with motorcycle gangs such as the Hell's Angels. It was inevitable. Such gangs are closely tied into the custom parts business. Sato remembers this as a very exciting and stimulating time in his life. Sometimes there would be parties thrown in honor of his visits. Weekends would be spent riding. "There are lots of motorcycle gangs on the mainland," he says. ''Not just Hell's Angels. Some of them are what they call Saturday night riders. A guy who works a regular job during the week, and on the weekend he puts on his jacket, gets on his motorcycle and rides." Ah, yes. We are all familiar with the sight. A pack of motorcycle bad boys cruising the highways. They wear headbands and decals and their girlfriends are strapped to their backs. For most of us, the sight It is somewhat disconcerting are ,but for a member of the pack it is a reason to be. "It's a natural high I says Sato." There you are on your motorcycle. It's something you've made yourself. And the reason you've made it is to ride it. It responds to your sincerity. I wouldn't say it's like a woman, but in some ways the relationship is that close."

Sato assures me that in no way is a motorcycle a substitute for a woman. He is a married man-a father. Nevertheless,the analogy springs open a valve in his heart: "...A man wants a woman to be a certain way. He wants her to be perfect. He says, 'if only she would wear her hair or her clothes a little different In the case of a motorcycle, you can make it what you want it to be. And if you take care of it, it will reward you. It will give you that Satisfaction."

I tell Sato that many men draw the same comparisons between women and cars. What's so different about motorcycles? "How do you prefer a woman?" he responds 'With or without clothes?" It was partly because of a woman I that Sato quit the interior design business. The owner of the company wanted him to marry his daughter. That would have put Sato, who was 24 at the time, in the position of being next in line to run the company. He wanted no part of it. The basic problem with the interior design work," he says, is that I would do what I considered to be an excellent design. My company would then show it to the client-who would make these terrible changes. "So you couldn't stand the artistic compromise? Sato nods. "The girl wasn't that great, either. '' "In Japanese society when you quit a job like that, it's not easy to find a job again. It's not like here where you quit a job and go find another one. When I quit that job, I knew I had to make it on my own. It was time to pursue a dream he had always had of opening up his own custom shop in the U.S. Sato lowered one of his motorcycles onto a boat and came to Hawaii. He landed a job in a shop called Motorcycle Alley. After a short stint there, he worked for Bobby Nakasone at the Iron Horse Den. He credits Nakasone with teaching him a lot of what hg knows about customizing. But he didn't have a work visa. Eventually, he had to return to Japan. His dream would have to wait. Back in Japan, Sato's parents owned an apartment building with some land next to it.

Sato erected a make-shift shop there and hung out his shingle-Motorcycle Den. "The first year-and-a-half I had barely enough business to survive," he says. He would paint racing cycles, or put on fiberglass cowlings that came up around the riders, or make customized fenders for the cars of teenage gangs. But there was no custom Harley work. Nevertheless, he had his calling card, and he used it to find out who was doing the very best air brush work, the very best welding-all the different technologies involved with motorcycles. This was 1977, and Sato was 27 years old. As he saw what different people were doing, he was amazed at the level of technology that existed in Japan. In that year and a half, he sensed he could make it.

"The first year-and-a-half I had barely enough business to survive," he says. He would paint racing cycles, or put on fiberglass cowlings that came up around the riders, or make customized fenders for the cars of teenage gangs. But there was no custom Harley work. Nevertheless, he had his calling card, and he used it to find out who was doing the very best air brush work, the very best welding-all the different technologies involved with motorcycles. This was 1977, and Sato was 27 years old. As he saw what different people were doing, he was amazed at the level of technology that existed in Japan. In that year and a half, he sensed he could make it.

Soon after this he began entering motorcycle shows and was discovered by the Japanese press. Shukan Asahi magazine, Japan's Saturday Evening Post, did a feature on him and further media exposure followed. With it, his business prospered. The Tokyo shop-which like his Honolulu shop is called Motorcycle Den-now occupies one three-story building and half of the two-story building that adjoins it. The Den specializes in the sale of custom Harley Davidson parts, in building custom chopper scooters, and in the total restoration of vintage Harleys for sale to collectors. The Den also produces original parts and cooperates in design fabrication of prototype parts for major motor cycle companies and FI racing car makers. Motorcycles such as the Titan have brought Sato his greatest measure of fame, but it is the parts he designs and builds that are his greatest source of revenue. "If some sheik from Arabia says, 'Here is $100,000. I want the ultimate motorcycle,' I can do the job,'' he says. "'But the parts are the real nuts and bolts of this business." His stainless steel push-rod covers, for example, do not rust, or leak oil, and are easy to clean. ''They may cost three or four times as much as a regular part, but they last a long time," he says. "You can put one in a Harley for five years, take it out and put it in your next Harley." If you want to upgrade your motorcycle with parts that will last longer, Sato has the goods.

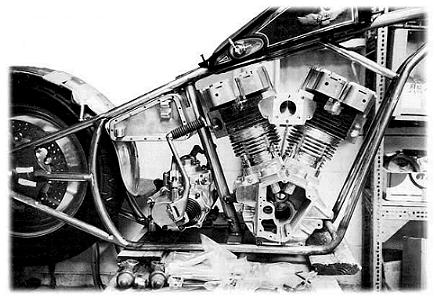

Sato's Honolulu shop, opened in 1983, has been a first step toward realizing his dream of opening a shop on the U.S. Mainland. But California is the promised land. To penetrate this market, he will unveil the Titan at motorcycle shows, demonstrating to the world just how good a motorcycle he can create,and then introduce his parts.

"When you look at the motorcycle business in the United States, the shops all seem to be doing the same thing with their customizing," he says. They treat the block the same way. The exhaust pipe is basically the same. Most people who are in this business take one 'look at what I'm doing and say, 'Why are you going to all this trouble to make these parts this way?

"The procedures by which Sato's parts are designed and made are very time consuming, very exact and very expensive. He shows me the front fork kit from a typical motorcycle (the part that connects the handle bars to the front wheel)."You use this for three years, the chrome comes off," he says. "The steel is weak. It bends, goes out of alignment." He then shows me his own front fork. It has liter-ally been sculpted from a block of the best stainless steel. He tells me that to make such a part in Japan would cost $18,000. "These bearings here," he says, "these are airplane bearings. They'll take up to 2000 pounds per inch of pressure. So nothing is ever going to go wrong with these bearings. They are made from absolutely the best kind of stainless steel for the work that a motorcycle has to do. This is the ultimate way these parts can be made."This is a 100 percent pure titanium muffler. In world class, top professional motorcycle racing, they use a mixture of 70 percent titanium and 30 percent steel. Why make a 100 percent titanium muffler? One of the special characteristics of titanium is that when it burns it makes an incredibly beautiful rainbow out of the exhaust...jewelers are taking titanium pendants and firing them up to 700 or 800 degrees to get this incredible rainbow effect and selling it as high-priced jewelry."

Listening to Sato, I am reminded of the book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Actually, the book has very little to do with Zen or motorcycles but sato seems to be the personification of what the title suggests. He says he has never heard of the book, but that Zen and martial arts were a part of his Japanese upbringing. He remembers these disciplines all stressed the importance of correct breathing and concentration.

He tells the story of how one day he brought a motorcycle part into the shop. The part was five millimeters thick. He wanted to machine it down to four millimeters. "If you have a machine,- he says, "it will take off the one millimeter no problem. But if you want to take off one millimeter on all faces of the part, by hand, it takes tremendous concentration '

Could it be done? Sato wasn't sure. He decided to try and came within 1/200 of a millimeter tolerance. ''When a human being concentrates, he can accomplish amazing things:' he says. "When you are finely tuning a machine part, or completing a fine paint job, it requires such intense concentration. So intense that after a minute you might be exhaust-ed.... If you don't breathe correctly, you don't get relief from your fatigue." Sato is not a follower of any religion, but he allows that in some subtle way Zen has affected his outlook on life. He admits it probably has a lot to do with the clarity with which he has always seen his way.

Sato is now poised to achieve his dream of opening up his own custom shop on the U.S. Mainland. He has his work visa. The Titan is the key. Of the machine, he says ,It's a simple design, efficient, restrained.

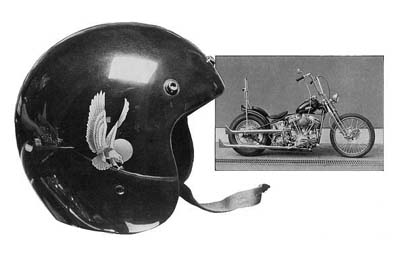

It's the logical next step for someone who is really into motorcycles. It's my masterpiece-but already I have ideas to improve it for the next one." I look over at the Titan and then back at sato, and then at his motorcycle helmet, which is resting next to me on the counter. The helmet has more than ten coats of traditional Japanese lacquer, taken from a tree. "The thing about lacquer is that is lasts longer than any other finish," he says. "I got the idea looking at old armor in a Japanese museum. I thought, 'There it is. It's 400 years old and still looks good. It must be the lacquer. "I look closely at the helmet. As a result of being exposed to sunlight it has changed colors-from black to a beautifully polished shade of purple. It is the helmet of an artist and a warrior, the helmet of a man who on a motorcycle straddles two very different cultures. painted onto its right side, an eagle soars across a rising sun.